Jetpack to the Top: Advancing Your Career as a Product Designer

How to Master Product Thinking and Tackle Complex Projects

As a designer, making the leap from junior to senior positions can be challenging. However, by understanding the key skills and attributes that are often sought after in senior-level designers, you can increase your chances of getting promoted. Through my experience mentoring designers and helping them advance in their careers, I’ve noticed certain patterns in the traits and abilities of those who have successfully made the transition to a senior role.

As design roles continue to evolve and expand beyond traditional UX, the skills and attributes sought after by hiring managers have also shifted. Among the core technical abilities valued by employers are proficiency in visual design, interaction design, and product thinking. As a junior or intermediate designer, you may focus on honing your execution skills and collaboration abilities. In fact, the technical skill gap between intermediate and senior designers is less prominent than you’d think. Instead, as you progress to a senior level, it’s more important to develop strong product thinking and communication skills.

Beyond product thinking, you also need to demonstrate your capacity to handle ambiguous and large-scoped projects. With the right development and practice, you can become a well-rounded senior designer who is equipped to handle any challenge that comes your way.

In this article, I’ll share these insights and provide actionable steps for developing the skills and mindset needed to move up in your field.

Communicating business value with product thinking

Product thinking is essentially a designer’s ability to connect user goals with business goals. One of the most important aspects of product thinking is the ability to communicate the ‘business value’ of a design decision to your stakeholders. Talking about user empathy and usability sounds abstract and confuses non-designers. Therefore learning the ‘common language’ of business value gives you a massive competitive advantage in influence and ownership.

Nearly every single project a business invests in has the underlying goal of either profit or growth. Profit is broken down into ‘increasing revenue’ and ‘decreasing costs’. Growth is broken down into ‘customer (user) acquisition’ and ‘customer (user) retention’).

The best product thinkers are able to clearly connect the work they do with one of these four ‘major business goals’. To do this effectively, it’s important to have a basic understanding of metrics, and know how to iterate on your designs to improve those metrics. Let’s begin with an overview of ‘macro-conversions’ and ‘micro-conversions’.

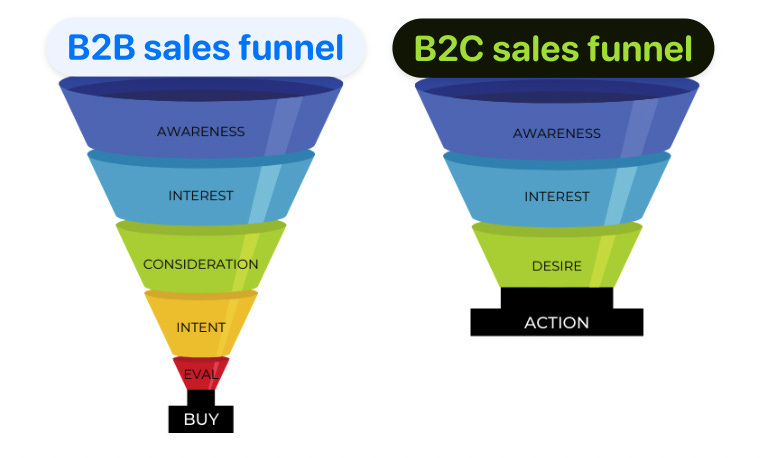

B2B vs. B2C business goals

B2B (business-to-business) and B2C (business-to-consumer) companies have different business goals that they focus on. Therefore, you may want to focus on creating business value based on the type of company you work for.

Broadly speaking, B2B companies tend to focus on profit since they typically have much larger customer lifetime value (LTV). They often measure success using annual recurring revenue (ARR) and acquisition is typically done through sales instead of growth and marketing (so less design influence here). On the other hand, B2C companies tend to focus on growth, i.e. acquiring and retaining customers and users.

Understanding metrics

All product metrics can be classified as either macro-conversions or micro-conversions. Macro-conversions refer to the major actions that a user takes within your product, such as making a purchase (which connects to the revenue business goal) or signing up for a service (which connects to the acquisition business goal).

Micro-conversions, on the other hand, refers to smaller actions that a user takes on a website, such as viewing a product page, adding an item to a shopping cart, or filling out a contact form. These smaller micro-conversation actions are the steps that lead up to a macro-conversion. Micro-conversions can give insight into how users interact with a product (i.e., friction and drop-off points) before completing a macro conversion.

From a designer's point of view, it’s normally difficult to influence macro-conversions directly without considering the associated micro-conversions. In other words, designers should focus on framing their design rationale around improving micro-conversions and connecting them to macro-conversions and ultimately the overarching business goal.

Example

For example, if you have an e-commerce website, a macro conversion would be a user making a purchase while a micro conversion would be viewing a product detail page. Let’s say you’re tasked with designing the product detail page for Walmart’s e-commerce experience. From user research, you’ve deduced that users have trouble making purchase decisions for expensive products with many SKUs.

Based on that insight, you have 5 ideas on how to improve the ‘micro-conversions’ of reducing ‘bounce rate’ and increasing ‘add to cart’ click-through rate. Take a moment and imagine how you would convince your team to implement your suggestions despite potentially expensive engineering costs.

Here’s how I would hypothetically connect my ideas: If we…(list ideas)

…add ‘best seller’ and ‘reduced price’ tags to relevant product pages

…add a feature to allow customers to zoom in on the product photos

…add context about free shipping if eligible

…add context about the product rating and reviews

…add context about our return policies if eligible

…then customers will be able to make a purchase decision faster and add the product to the cart because it addresses the most common customer concerns and hesitations uncovered from our user research sessions

…which will reduce page ‘bounce rate’ and increase “add to cart” ‘click-through rate’ (micro-conversions)

…which will increase the ‘checkout conversion rate’ and ‘average cart total ($)’ (macro-conversions)

…which will ultimately increase the company’s revenue (business goal)

Stringing this all together, you can use this as a template: “If we [idea] then customers will be more likely to make a decision faster and add the product to the cart because [specific rationale], we will improve [micro-conversions], which will improve [macro-conversions], and ultimately help us with [business goal].

The next level

Once you’ve developed your product thinking and communication skills to a sufficient level, the next step is to demonstrate your ability to handle more scope and ambiguity. In most tech companies, your seniority is correlated with the scope and ambiguity of the projects you work on.

As you move up the ranks in a tech company, you will be responsible for solving more ambiguous problems and be responsible for a wider scope. This is what Kun Chen referred to in his article about the differences between ‘levels’ at tech companies. Let’s break down exactly what scope and ambiguity mean for designers.

Expanding scope of ownership

The degree of scope refers to the level of responsibility and ownership within a project. At a junior to intermediate level, your scope may include designing a single screen or feature, such as a sign-up screen, to a multi-screen flow such as an onboarding experience. It can also include designing for different platforms, such as iOS, Android, and web.

At an intermediate to senior level, the focus shifts to how the design decisions impact other teams and the user journey as a whole. The designer starts to identify opportunities for collaboration and eliminate duplicate work and may be responsible for large product areas or entire products.

At senior to staff levels, the designer’s responsibility and scope expand to looking at problems from a holistic systems level. They are responsible for understanding the specific situation and constantly expanding their scope and sphere of influence by looking at design problems from higher degrees of abstraction. For example, at this level, a designer may be responsible for the overall user experience across all channels of a product, and not just a single screen or feature.

Working on more ambiguous projects

The degree of ambiguity refers to how open-ended and non-prescriptive the tasks are. At a junior to intermediate level, tasks typically have clear requirements and scope. For example, redesigning a sign-up flow with specific requirements and constraints.

As you progress to an intermediate to senior level, you’ll no longer get explicit requirements for your projects. Instead, you’ll be given specific problems to solve or specific metrics to drive, such as increasing sign-up conversion rate by 10 percent or driving 50,000 new users through the sign-up flow this quarter.

At the senior to staff level, you are expected to identify problems and opportunities, propose a vision, and solicit internal support. For example, you might conduct your own investigations and discover that there is an 80 percent bounce rate on a critical page that you’re driving traffic to through ad spend. Once you identify an opportunity to create significant business value, you would then rally internal support around your vision and lead the entire project. At this level, you are expected to take ownership of the problem and push for alignment, instead of being told what to do.

How to get started

So now you’re probably wondering how you can expand your scope and work on more ambiguous problems at work. One way to do this is by partnering with product managers as a thought partner. When working with junior designers, product managers often have to come up with ideas to achieve certain business goals, which they then translate into specific requirements for designers.

For example, if a product manager asks you to redesign a sign-up page to make it more aesthetic, by understanding the core problem behind the request, you can propose a better solution instead. Using your UX knowledge (i.e., understanding of interaction costs), you could suggest improving the messaging throughout the entire sign-up conversion funnel, which would likely be more impactful in increasing sign-ups.

Another way to expand your scope is by leading cross-team initiatives. This can be done by identifying related or adjacent projects from other teams and aligning everyone’s vision to reduce duplicating work. Using the example above, if you discover that the pages before the sign-up form have high bounce rates, you could conduct research and form a hypothesis that the problem may be due to a combination of slow loading times, confusing messaging, and unclear call-to-actions. You could then present your findings to the teams responsible for those parts of the experience and coordinate efforts to solve the root cause of the problem, instead of implementing a superficial solution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, as a product designer, it’s essential to develop the foundational skills required to be able to handle more scope and ambiguity, which are ultimately the key factors in determining your seniority level in a tech company. Instead of mindlessly grinding your technical skills or trying to hit all the checkboxes on an internal promotion rubric, it’s much more worthwhile to develop these skills as they would allow you to thrive in any environment.

Please share this article with other designers who might find it helpful!

I also have a Youtube channel helping designers with interview prep and product thinking. If you’d like to schedule a 1–1 mentorship session with me, you can book them here.

Helpful readings

Learn how to structure product experiments as a designer

Learn about interaction costs for articulating micro-conversion rationale

Learn how to improve retention by reducing TTV and the Hook Model

Learn how to increase acquisition by writing better content for your landing pages